Science Fiction

Dictionary

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

Sheepskin Parchment Helped Medieval Lawyers Prevent Fraud

It turns out that using sheepskin parchment was a choice that may have helped early modern lawyers, and even their medieval counterparts, in preventing fraud in legal documents.

The problem of fraudulent documents and even deep fake photographs and videos is now much worse in the electronic age. George Orwell clearly describes the problem in 1984, using a key word from medieval times, "All history was a palimpsest, scraped clean and reinscribed exactly as often as was necessary."

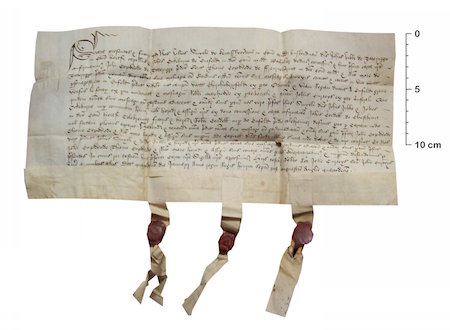

(Sheepskin Parchment )

Sheep deposit fat in-between the various layers of their skin. During parchment manufacture, the skin is submerged in lime, which draws out the fat leaving voids between the layers. Attempts to scrape off the ink would result in these layers detaching—known as delamination—leaving a visible blemish highlighting any attempts to change any writing.Sheepskin has a very high fat content, accounting for as much as 30 to 50 percent, compared to 3 to 10 percent in goatskin and just 2 to 3 percent in cattle. Consequently, the potential for scraping to detach these layers is considerably greater in sheepskin than those of other animals.

The work was carried out by academics from the University of Exeter and Universities of York and Cambridge.

Dr. Sean Doherty, an archaeologist from the University of Exeter who led the study, said: "Lawyers were very concerned with authenticity and security, as we see through the use of seals. But it now appears as though this concern extended to the choice of animal skin they used too".

Dr. Doherty said: "The text written on these documents is often considered to be of limited historic value as the majority is taken up by formulaic rubric. However modern research techniques mean we can now not only read the text, but the biological and chemical information recorded in the skin. As physical objects they are an extraordinarily molecular archive through which centuries of craft, trade and animal husbandry can be explored."

The 12th century text Dialogus de Scaccario—written by Richard FitzNeal, Lord Treasurer during the reigns of Henry II and Richard I—instructs the use of sheepskin for royal accounts as "they do not easily yield to erasure without the blemish being apparent".

In the 17th century when paper was common, Chief Justice Sir Edward Coke wrote of the necessity that legal documents were written on parchment "for the writing upon these is least liable to alterations or corruption".

(Via PhysOrg.)

Science fiction writers are fascinated with writing materials, as you might imagine; in his 1960 novel Dorsai!, Gordon R. Dickson in particular devised the idea of a paper contract that could not be altered in any way once written:

The single sheet he held, and even the words and signatures upon it, were all integral parts of a single giant molecule which in itself was well-nigh indestructible and could not be in any way altered or tampered with short of outright destruction...

(Read more about Single Sheet Molecule)

You might want to read these past stories, before they are altered or the memory they are kept on is erased to make way for new content:

- eScroll Design Takes E-Books Way Back

What kind of electronic book would a time-traveler used to scrolls pick? - Reading A Scroll Burned To Charcoal

The effort to read the ancient text began when researchers at the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) in Jerusalem took high resolution x-rays... - Diamond Light Source Illuminates Manuscripts

A reading light so powerful that scientists will be able to read books without even opening them. - Electronic Erasable Paper - Xerox Seeks E-Palimpsest

Electronic reusable paper could reduce waste; as many as 40% of paper copies in offices are used for only a single day.

Scroll down for more stories in the same category. (Story submitted 3/15/2021)

Follow this kind of news @Technovelgy.| Email | RSS | Blog It | Stumble | del.icio.us | Digg | Reddit |

Would

you like to contribute a story tip?

It's easy:

Get the URL of the story, and the related sf author, and add

it here.

Comment/Join discussion ( 0 )

Related News Stories - (" Culture ")

A Remarkable Coincidence

'There is a philosophical problem of some difficulty here...' - Arthur C. Clarke, 1953.

Is It Time To Forbid Human Driving?

'Heavy penalties... were to be applied to any one found driving manually-controlled machines.' - Bernard Brown, 1934.

Indonesian Clans Battle

'The observation vehicle was of that peculiar variety used in conveying a large number of people across rough terrain.' - Jack Vance (1952)

Liuzhi Process Now In Use In China

'He was in a high-ceilinged windowless cell with walls of glittering white porcelain.' - George Orwell, 1984.

Technovelgy (that's tech-novel-gee!) is devoted to the creative science inventions and ideas of sf authors. Look for the Invention Category that interests you, the Glossary, the Invention Timeline, or see what's New.

Science Fiction

Timeline

1600-1899

1900-1939

1940's 1950's

1960's 1970's

1980's 1990's

2000's 2010's

Current News

The New Habitable Zones Include Asimov's Ribbon Worlds

'...there's a narrow belt where the climate is moderate.'

Can One Robot Do Many Tasks?

'... with the Master-operator all you have to do is push one! A remarkable achievement!'

Atlas Robot Makes Uncomfortable Movements

'Not like me. A T-1000, advanced prototype. A mimetic poly-alloy. Liquid metal.'

Boring Company Drills Asimov's Single Vehicle Tunnels

'It was riddled with holes that were the mouths of tunnels.'

Humanoid Robots Tickle The Ivories

'The massive feet working the pedals, arms and hands flashing and glinting...'

A Remarkable Coincidence

'There is a philosophical problem of some difficulty here...'

Cortex 1 - Today A Warehouse, Tomorrow A Calculator Planet

'There were cubic miles of it, and it glistened like a silvery Christmas tree...'

Perching Ambush Drones

'On the chest of drawers something was perched.'

Leader-Follower Autonomous Vehicle Technology

'Jason had been guiding the caravan of cars as usual...'

Golf Ball Test Robot Wears Them Out

"The robot solemnly hit a ball against the wall, picked it up and teed it, hit it again, over and again...'

Boring Company Vegas Loop Like Asimov Said

'There was a wall ahead... It was riddled with holes that were the mouths of tunnels.'

Rigid Metallic Clothing From Science Fiction To You

'...support the interior human structure against Jupiter’s pull.'

Is The Seattle Ultrasonics C-200 A Heinlein Vibroblade?

'It ain't a vibroblade. It's steel. Messy.'

Roborock Saros Z70 Is A Robot Vacuum With An Arm

'Anything larger than a BB shot it picked up and placed in a tray...'

A Beautiful Visualization Of Compact Food

'The German chemists have discovered how to supply the needed elements in compact, undiluted form...'

Bone-Building Drug Evenity Approved

'Compounds devised by the biochemists for the rapid building of bone...'