Science Fiction

Dictionary

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

Store Extra Energy In Liquid Air

The UK's Institution of Mechanical Engineers has announced that liquid air can be used to store excess energy generated from renewable sources. For example, wind farms generate power at night, but since demand is low at that time, the energy may be wasted.

When demand increases the next day, the liquid air can be warmed to drive a turbine, thereby giving the energy back.

Engineers say the process can achieve an efficiency of up to 70%.

This work derives from the work of Britainís Peter Dearman, who invented a liquid air engine to power vehicles as seen in the following video.

The process follows a number of stages:

Highview believes that, produced at scale, their kits could be up to 70% efficient, and IMechE agrees this figure is realistic.

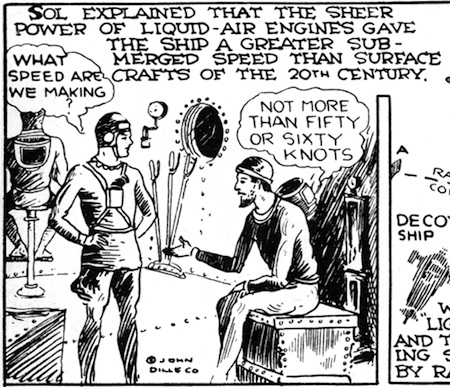

Science fiction fans of yesteryear would not find this idea hard to believe. The idea of storing energy in liquid air and then using it to power engines was used in Buck Rogers in the 25th Century.

(Buck Rogers in the 25th Century)

Via BBC. Thanks to Winchell Chung of Project Rho for the tip and the reference on this story.

Scroll down for more stories in the same category. (Story submitted 10/2/2012)

Follow this kind of news @Technovelgy.| Email | RSS | Blog It | Stumble | del.icio.us | Digg | Reddit |

Would

you like to contribute a story tip?

It's easy:

Get the URL of the story, and the related sf author, and add

it here.

Comment/Join discussion ( 0 )

Related News Stories - (" Engineering ")

Can One Robot Do Many Tasks?

'... with the Master-operator all you have to do is push one! A remarkable achievement!' - Robert Sheckley, 1952.

Roborock Saros Z70 Is A Robot Vacuum With An Arm

'Anything larger than a BB shot it picked up and placed in a tray...' - Robert Heinlein, 1956.

Secret Kill Switch Found In Yutong Buses

'The car faltered as the external command came to brake...' - Keith Laumer, 1965.

The Desert Ship Sailed In Imagination

'Across the ancient sea floor a dozen tall, blue-sailed Martian sand ships floated, like blue smoke.' - Ray Bradbury, 1950.

Technovelgy (that's tech-novel-gee!) is devoted to the creative science inventions and ideas of sf authors. Look for the Invention Category that interests you, the Glossary, the Invention Timeline, or see what's New.

Science Fiction

Timeline

1600-1899

1900-1939

1940's 1950's

1960's 1970's

1980's 1990's

2000's 2010's

Current News

The New Habitable Zones Include Asimov's Ribbon Worlds

'...there's a narrow belt where the climate is moderate.'

Can One Robot Do Many Tasks?

'... with the Master-operator all you have to do is push one! A remarkable achievement!'

Atlas Robot Makes Uncomfortable Movements

'Not like me. A T-1000, advanced prototype. A mimetic poly-alloy. Liquid metal.'

Boring Company Drills Asimov's Single Vehicle Tunnels

'It was riddled with holes that were the mouths of tunnels.'

Humanoid Robots Tickle The Ivories

'The massive feet working the pedals, arms and hands flashing and glinting...'

A Remarkable Coincidence

'There is a philosophical problem of some difficulty here...'

Cortex 1 - Today A Warehouse, Tomorrow A Calculator Planet

'There were cubic miles of it, and it glistened like a silvery Christmas tree...'

Perching Ambush Drones

'On the chest of drawers something was perched.'

Leader-Follower Autonomous Vehicle Technology

'Jason had been guiding the caravan of cars as usual...'

Golf Ball Test Robot Wears Them Out

"The robot solemnly hit a ball against the wall, picked it up and teed it, hit it again, over and again...'

Boring Company Vegas Loop Like Asimov Said

'There was a wall ahead... It was riddled with holes that were the mouths of tunnels.'

Rigid Metallic Clothing From Science Fiction To You

'...support the interior human structure against Jupiterís pull.'

Is The Seattle Ultrasonics C-200 A Heinlein Vibroblade?

'It ain't a vibroblade. It's steel. Messy.'

Roborock Saros Z70 Is A Robot Vacuum With An Arm

'Anything larger than a BB shot it picked up and placed in a tray...'

A Beautiful Visualization Of Compact Food

'The German chemists have discovered how to supply the needed elements in compact, undiluted form...'

Bone-Building Drug Evenity Approved

'Compounds devised by the biochemists for the rapid building of bone...'