Science Fiction

Dictionary

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

Do You Hold Robots Morally Accountable?

Would you hold a robot morally accountable for its behavior? The people at the Human Interaction With Nature and Technological Systems (HINTS) Lab at the University of Washington, in Seattle, wanted to know.

Autonomous robots are very close to being able to interact with human beings in a variety of ways. The folks at HINTS have published two large studies exploring whether humans view robots as moral entities.

Their intent was to study a scenario like the following:

A typical interaction is shown in the video; read the description below for an outline of the procedure.

Consider a scenario in which a domestic robot assistant accidentally breaks a treasured family heirloom; or when a semi-autonomous robotic car with a personified interface malfunctions and causes an accident; or when a robot-fighting entity mistakenly kills civilians. Such scenarios help establish the importance of the following question: Can a robot now or in the near futureósay 5 or 15 years outóbe morally accountable for the harm it causes?

(Moral accountability of robots study)

The first study from HINTS investigated whether humans hold a humanoid robot morally accountable for harm that it causes. The robot in question is Robovie, the little guy (little piece of equipment?) in the picture above, who was secretly being controlled by humans throughout the duration of the experiment. The experiment itself was designed to put a hapless human in a situation where they would experience Robovie making a false statement, and see how they'd react: would Robovie be responsible, or simply a malfunctioning tool?To figure this out, human subjects were introduced to Robovie, and the robot (being secretly teleoperated) made small talk with them, executing a carefully scripted set of interactions designed to establish that the robot was socially sophisticated and capable to form an increasingly social relationship between robot and human. Then, Robovie asked the subject to play a visual scavenger hunt game, with $20 at stake: the subject would attempt to find at least seven items, and if Robovie judged them to be successful (that's an important bit), within a 2-minute time limit, they'd get the money.

The game, of course, was rigged.

Overall, the study, funded by the National Science Foundation, found that:

65% of the participants attributed some level of moral accountability to Robovie for the harm that Robovie caused the participant by unfairly depriving the participant of the $20.00 prize money that the participant had won. ...We found that participants held Robovie less accountable than they would a human but more accountable than they would a machine. Thus as robots gain increasing capabilities in language comprehension and production, and engage in increasingly sophisticated social interactions with people, it is likely that many people will hold a humanoid robot as partially accountable for a harm that it causes.

Science fiction writers have spent some time exploring these topics. In the sequel to Stanley Kubrick's 2001, Dr. Chandra learns at last why the HAL-9000 computer exhibited unusual behavior in the earlier film 2001: A Space Odyssey. (SPOILER!)

(From 2010 - HAL tries to lie)

"... he was given full knowledge of the two objectives and was told not to reveal these objectives to Bowman or Poole. He was instructed to lie...The situation was in conflict with the basic purpose of HAL's design - the accurate processing of information without distortion or concealment. He became trapped... HAL was told to lie - by people who find it easy to lie.

The Bolo autonomous tanks from Keith Laumer's stories evolved to become robotic exemplars of military virtue.

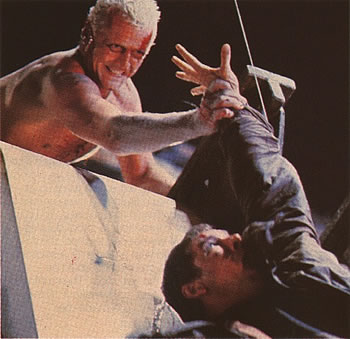

In the 1982 movie Blade Runner, the replicant (non-robotic, but an artificial human) Roy Batty is given the choice to let his enemy, the human detective Rick Deckard, die, Batty instead chooses to save him.

(Roy Batty debates saving Rick Deckard in Blade Runner)

Ethical dilemmas for robots are as old as the idea of robots in fiction. Ethical behavior (in this case, self-sacrifice) is found at the end of the 1921 play Rossum's Universal Robots, by Czech playwright Karel Čapek. This play introduced the term "robot".

Update: For a hilarious counterpoint to this article, take a look at this video from the British TV series Red Dwarf in which Kryten the robot is taught to lie. You'll love Kryten's reasons for wanting to lie, and Dave's reasons for teaching him. End update.

Update: 04-Dec-2024: See the entry for Robot AI Driven Mad from Liar (1941) by Isaac Asimov. End update.

Via IEEE Spectrum

Scroll down for more stories in the same category. (Story submitted 4/27/2012)

Follow this kind of news @Technovelgy.| Email | RSS | Blog It | Stumble | del.icio.us | Digg | Reddit |

Would

you like to contribute a story tip?

It's easy:

Get the URL of the story, and the related sf author, and add

it here.

Comment/Join discussion ( 1 )

Related News Stories - (" Robotics ")

Atlas Robot Makes Uncomfortable Movements

'Not like me. A T-1000, advanced prototype. A mimetic poly-alloy. Liquid metal.' - James Cameron, 1991.

Humanoid Robots Tickle The Ivories

'The massive feet working the pedals, arms and hands flashing and glinting...' - Herbert Goldstone, 1953.

Golf Ball Test Robot Wears Them Out

"The robot solemnly hit a ball against the wall, picked it up and teed it, hit it again, over and again...' - Frederik Poh, 1954.

PaXini Supersensitive Robot Fingers

'My fingers are not that sensitive...' - Ray Cummings, 1931.

Technovelgy (that's tech-novel-gee!) is devoted to the creative science inventions and ideas of sf authors. Look for the Invention Category that interests you, the Glossary, the Invention Timeline, or see what's New.

Science Fiction

Timeline

1600-1899

1900-1939

1940's 1950's

1960's 1970's

1980's 1990's

2000's 2010's

Current News

The New Habitable Zones Include Asimov's Ribbon Worlds

'...there's a narrow belt where the climate is moderate.'

Can One Robot Do Many Tasks?

'... with the Master-operator all you have to do is push one! A remarkable achievement!'

Atlas Robot Makes Uncomfortable Movements

'Not like me. A T-1000, advanced prototype. A mimetic poly-alloy. Liquid metal.'

Boring Company Drills Asimov's Single Vehicle Tunnels

'It was riddled with holes that were the mouths of tunnels.'

Humanoid Robots Tickle The Ivories

'The massive feet working the pedals, arms and hands flashing and glinting...'

A Remarkable Coincidence

'There is a philosophical problem of some difficulty here...'

Cortex 1 - Today A Warehouse, Tomorrow A Calculator Planet

'There were cubic miles of it, and it glistened like a silvery Christmas tree...'

Perching Ambush Drones

'On the chest of drawers something was perched.'

Leader-Follower Autonomous Vehicle Technology

'Jason had been guiding the caravan of cars as usual...'

Golf Ball Test Robot Wears Them Out

"The robot solemnly hit a ball against the wall, picked it up and teed it, hit it again, over and again...'

Boring Company Vegas Loop Like Asimov Said

'There was a wall ahead... It was riddled with holes that were the mouths of tunnels.'

Rigid Metallic Clothing From Science Fiction To You

'...support the interior human structure against Jupiterís pull.'

Is The Seattle Ultrasonics C-200 A Heinlein Vibroblade?

'It ain't a vibroblade. It's steel. Messy.'

Roborock Saros Z70 Is A Robot Vacuum With An Arm

'Anything larger than a BB shot it picked up and placed in a tray...'

A Beautiful Visualization Of Compact Food

'The German chemists have discovered how to supply the needed elements in compact, undiluted form...'

Bone-Building Drug Evenity Approved

'Compounds devised by the biochemists for the rapid building of bone...'